Words and photography by Josie Porter, Art by Leela Stoede.

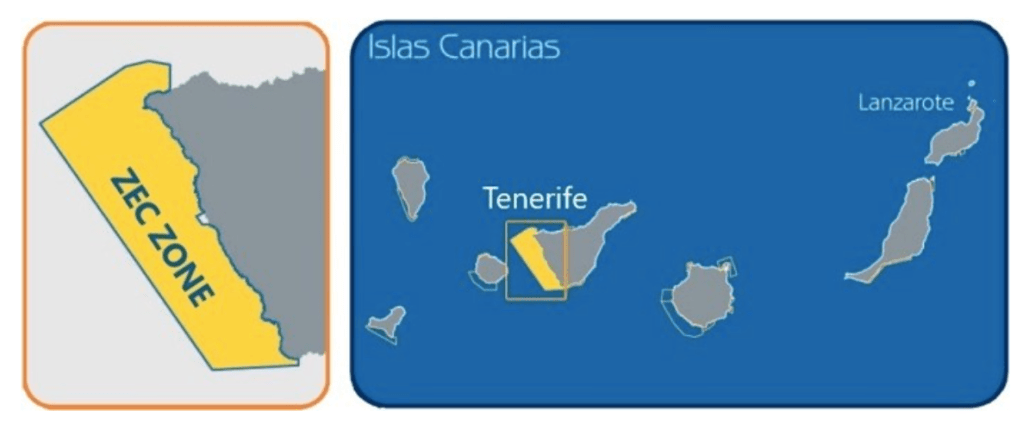

Sixty-two Miles from the African coast sits a Spanish archipelago. Dusty and sandy, the Canary Islands are so close to Morocco that the Sahara sands often whip up and pass over to the Canaries. Yet they are also territories of the European Union, the largest, most populous, and most highly visited of all the islands. Tenerife, and its western coast specifically, is a region whose society, industry, and culture is built on tourism. From Spanish food to sun beds and bottomless drinks, Costa Adeje provides the classic British all-inclusive holiday. In fact, walking around Costa Adeje (the western coast), you can hear a multitude of British accents – Mancunian in the pharmacy, Essex in the bar, Northern Irish in the supermarket. Once an indigenous western African island, Tenerife is now a European tourist destination with around 6 million tourists each year.

With so many visitors, ecotourism is bound to be a popular part of holiday life. The western shore is known as the Teno-Rasca Marine Strip and is home to 28 species of cetaceans – whales, dolphins, and porpoises. The most common of which are short-finned pilot whales. With bulbous heads, round rostrums, and chubby builds, these creatures are captivating. They are between 4-6 metres and live to up to 60 years. Each whale I encountered had a distinct personality that was palpable from just moments of detection of a pod.

Whale and dolphin tours are a large part of the Tenerife experience. While in Tenerife completing my internship, I conducted multiple land surveys where I observed the number of boats entering and exiting the harbour. The most common boats were whale-watching sail boats, offering excursions to tourists. Undoubtedly, these tours are a vital part of life in Tenerife; it provides jobs, income, is an integral part of the economy, and raises awareness about the lives of cetaceans in the Teno-Rasca strip.

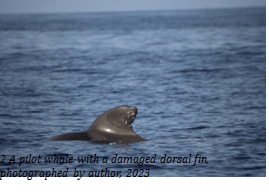

However, many of the pilot whales I observed had been negatively affected by tourism. Ferry boats transport tourists between various Canary Islands, crossing through territories pilot whales are known to occupy. Consequently, many whales are victims to collisions with these large tourist ferries, causing injury, and sometimes death. In other instances, smaller boats have collided with whales, causing damage to their dorsal fins.

Further, the plastic consumption caused by tourism is astounding. Residual microplastics wash up onto beaches in Tenerife, creating white, dotted lines in the sand that run along the coast. These microplastics float in the ocean, entering cetaceans’ systems and polluting their bodies with plastics and chemicals. While on the ocean watching for potential cetacean pods, part of an intern’s job was to spot for plastic pollution in the ocean. These pose a great threat to sea turtles in the region who confuse plastic bags for jellyfish, swallowing them whole and mistaking the feeling of being full with being well-nourished.

While pilot whales in the Canary Islands may seem geographically removed, their species are threatened globally. Here in Scotland, on the Isle of Lewis, over 50 pilot whales died in a mass stranding on a beach of the Scottish island. These cetaceans are not just a spectacle to witness on holiday; they occupy waters at home too.

So, what can we do?

To start, being aware of the products we use, where they come from, and where they end up is a big step. Simply being conscious about other life on Earth will start the kind of thinking required to make change. Additionally, reframing our perception helps; rather than seeing animals as living on our Earth, we can shift our perspectives to see it as a mutual cohabitation of a shared Earth. Humans do not dominate animals. By leaving our used products in their habitats we perpetuate the human/animal dichotomy that threatens these cetaceans and other vulnerable marine life. Working with nature will yield more effective results than pursuing human ingenuity to further human life rather than animals. Whether in an exclusive resort in the Atlantic Ocean, or on our domestic coasts, there are animals living with us that deserve our unconditional respect and protection.

Leave a comment