Words by Jadzia Allright, Art by Holly Brown.

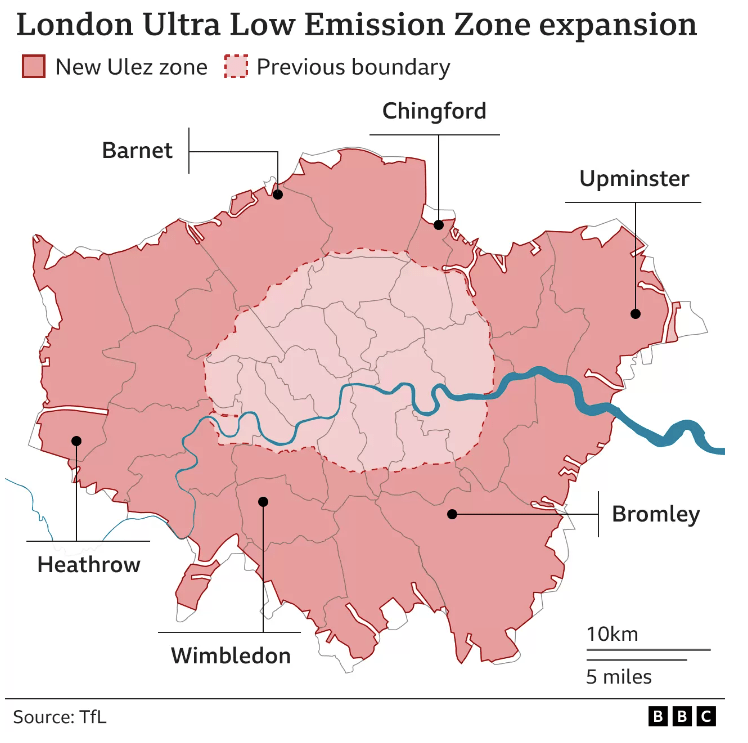

After the recent expansion in August 2023, the Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) and people’s reactions to it have been making headlines, as people complain, vandalise, and oppose the developments. The ULEZ was originally implemented in central London, before expanding to most of inner London in 2021. Now, it has expanded to include all London boroughs. Figure 1previous and current boundary. Within the ULEZ, drivers must pay £12.50 per day to drive in the zone their vehicle is non-compliant. This issue is also becoming a political battleground, as in a recent by-election, Conservatives won by 500 votes with the ULEZ as their main dispute.

A July survey noted that 32% of outer Londoners opposed the expansion of the ULEZ. Outer Londoners are more dependent on cars, as Figure 2 highlights, there is a lower concentration of public transport. The shortest journey on the Underground takes place in zone 1 which takes approximately 20 seconds, whilst the longest journey is in zone 9 and takes over 8 minutes. 44% of journeys involve a car in outer London, compared to only 17% in inner London.

A common misconception is the ULEZ is supposed to reduce carbon emissions. In reality, it is to clean up the air in cities. In many UK cities, air pollution exceeds the recommended limits by the World Health Organisation. WHO estimates there were approximately 4.2 million premature deaths related to air pollution in 2019. The two most prevalent gases are Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which cause and worsen asthma and heart conditions. The ULEZ has proved successful in central London, as after the implementation in 2019, NO2 levels were assessed to have fallen by 46% next to the roadside in 2022.

However, despite these supposed improvements, overall NO2 levels across London, away from roadsides, reduced by less than 3%. It’s estimated that the expansion of the ULEZ will only reduce NO2 levels by approximately 1.5% on average, which has made people wonder if all this hassle is worth it. The BBC notes that ‘the expansion of Ulez will have a relatively small effect on air pollution – and air quality would still fall short of WHO standards.’ Clean Air London has estimated that there have been 3600-4100 deaths due to human-made PM2.5 and NO2. City Hall research has suggested that 550,000 Londoners will have developed air-pollution-related diseases by 2050. Despite this, Alice Montague, who attributes a consistent cough to cycling to work in London, stated that since the ULEZ has been implemented the city’s air quality has noticeably improved.

One of the biggest points to oppose the ULEZ is concerning the impact on lower-income families. People have argued they were given insufficient notice, 9 months, before the scheme was implemented. The inability to drive cars will exacerbate inequalities and buying compliant cars on a whim is not an option. A scrappage scheme was created, but the scheme has numerous issues. For one, it only applies to those living in London; there is no financial support available for those living near London, who commute in. Furthermore, it is overwhelmed with those who can no longer drive their cars, and it is taking ages for compensation to be received. Additionally, the current cost-of-living crisis has meant that second-hand cars are more expensive than ever. Rishi Sunak has claimed that the ULEZ will hit working families, while Khan has stated that ‘clean air is a right not a privilege.’ Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debroah attributes her daughter’s death in 2013 to air pollution, thus supporting the ULEZ, but she also has concerns about lower-income families being able to sustain their lifestyles. The key is balance.

Even as people keep vandalising the cameras (used to regulate those entering a ULEZ), there has been no back down from the Mayor of London. Moreover, although people claim that London’s ULEZ scheme is one of the most restrictive in the world, looking at some of mainland Europe’s upcoming proposals to reduce air pollution, it seems extremely reasonable. For example, Paris is planning on banning private cars from most of the city by 2030, and Oslo is going to implement a zero-emission zone in the centre. Manchester is the next candidate for a ULEZ, but with a much smaller public transport network, this would exacerbate inequalities even further. The local government is reviewing its national bus programme to reduce emissions, possibly paving the way for a more intensive scheme.

While editing this article, the BBC reported that London’s air quality has improved significantly since the first instalment of a LEZ back in 2008. It is undeniable that socio-economic repercussions of the ULEZ are damaging and unfair to the communities affected. From an environmental and health perspective, the ULEZ was the right decision. What was not the right decision was the lack of help and struggles of bureaucracy that working-class people must endure.

Leave a comment