Words by Violet Melcher, Art by Zoë Graham.

We’ve all heard about the electric car being the vehicle of the future, but should it be? This past summer I had an internship with Ecology Action, a non-profit company in the states aimed at getting more households in low-income and disadvantaged communities electric cars. Participants could sign up for Ecology Action’s free program where we would work to get people qualified for rebates and grants in order to buy or lease electric cars at reduced costs.

A lot of the work I did included volunteering at events in nearby communities, talking to anyone who walked past our booth about the program we provided. Most of the time this would end up being a quick chat about what the future looked like for electric cars. However, when we went to vintage car shows or events in more right leaning towns, we’d get comments about how electric cars were “all talk.” Electric cars boasted these new innovative features and would cost you a fortune, only to run out of charge a third of the way into a weekend road trip. I started to memorize the statistics about the accessibility of chargers across the nation and how electric cars often ended up costing less than a generic car when you factor in costs throughout the lifespan of the vehicle. The vast majority of these questions were based on partial truths, that when fully explained, still left electric vehicles the best, greenest, and most cost-effective option. That said, a select few brought up how dependent electric vehicles are on lithium batteries. The reasoning behind this complaint isn’t as straight forward as the others.

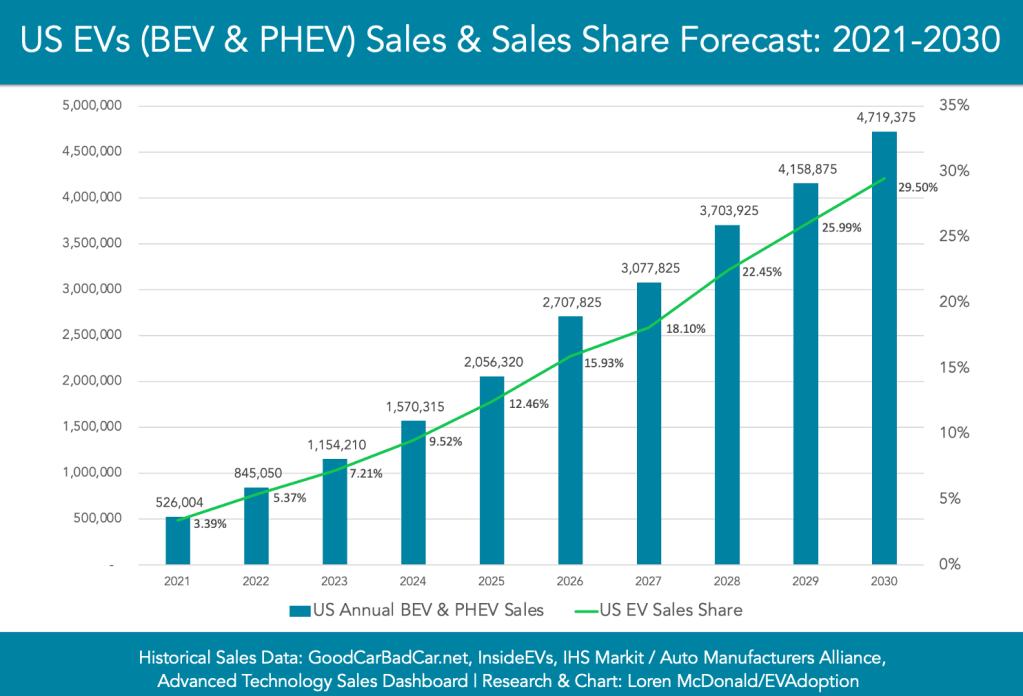

The graphic below shows both the past and projected increase in demand for electric vehicles going up to 2030. Even past the years shown on this graph, sources project that this growth will continue. Don’t get me wrong, this growth is a good thing. I truly believe that electric cars are a required aspect of a successful global future – but lithium batteries aren’t.

Figure 1: Electric Car Sales & Sales Shar Forecast 2021-2030 From McDonald, 2023

As electric vehicles steadily increase in popularity, the abundance of materials needed grows right along with it. In 2021, the demand for Automotive lithium-ion batteries was 330 GWh. However, in 2022 the demand increased by about 65%, requiring 550 GWh. This growth has no projected plateau.

The Argonne National Laboratory published data highlighting how a single lithium-ion car battery could contain 8 kg of lithium, 35 kg of nickel, 20 kg of manganese, and 14 kg of cobalt. These required minerals must be extracted or mined, making battery production a resource and emission heavy process especially when considering the projected industry growth.

Many claim this to be where generic cars pull ahead, that due to these mineral resources and the mechanisms required to extract them, your average petrol reliant car becomes the greener option. However, even with the dependance on minerals such as lithium, the emissions released in the making of an electric car are completely offset as the vehicle is driven. Moreover, the University of Michigan conducted a study, finding that between 1.4 to 1.9 years, the pollution equation completely evens out.

The emissions made in the production of an EV are offset by driving electric. Yet, they still require high amounts of mineral resources to even exist. How do we get to a point in time where electric cars don’t rely on large quantities of such complicated materials? Materials that not only need to be mined but also cause water shortages, pollution, and abuse to local communities.

Recycling and reusing batteries is a partial solution. However, with demand for these vehicles still increasing, recycling could at best account for half the nickel and lithium supply by 2050. Other than that, very few solutions currently exist. Many studies are being done to find alternatives to lithium batteries but none are close to production.

Though this is disheartening – it’s important to understand the complexities of electric vehicles. As someone who definitely went around only singing their praises, it’s beneficial to understand some of the drawbacks as well. Data still points to electric vehicles as being overall more environmentally sound than petrol reliant cars – but are they simply a lesser of 2 evils?

References

Carlton, Gregory J., and Selima Sultana. “Electric Vehicle Charging Station Accessibility and Land Use Clustering: A Case Study of the Chicago Region.” Journal of Urban Mobility, vol. 2, Dec. 2022, p. 100019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urbmob.2022.100019.

Crownhart, Casey. “How Old Batteries Will Help Power Tomorrow’s EVs.” MIT Technology Review, 2023, www.technologyreview.com/2023/01/17/1065026/evs-recycling-batteries-10-breakthrough-technologies-2023/#:~:text=Since%20demand%20is%20still%20rising. Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

EDF. “Benefits of Electric Cars on the Environment.” EDF, 2022, www.edfenergy.com/energywise/electric-cars-and-environment#:~:text=Research%20by%20the%20European%20Energy.

EPA. “Electric Vehicle Myths.” Www.epa.gov, 14 May 2021, http://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/electric-vehicle-myths.

Gordon, Meghan, and Maya Weber. “Global Energy Demand to Grow 47% by 2050, with Oil Still Top Source: US EIA.” Www.spglobal.com, 6 Oct. 2021, http://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/100621-global-energy-demand-to-grow-47-by-2050-with-oil-still-top-source-us-eia. Accessed 23 Apr. 2022.

Hausfather, Zeke. “Factcheck: How Electric Vehicles Help to Tackle Climate Change.” Carbon Brief, 13 May 2019, http://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-how-electric-vehicles-help-to-tackle-climate-change/.

IEA. “Trends in Batteries – Global EV Outlook 2023 – Analysis.” IEA, 2023, http://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/trends-in-batteries.

Kotak, Yash, et al. “End of Electric Vehicle Batteries: Reuse vs. Recycle.” Energies, vol. 14, no. 8, 16 Apr. 2021, p. 2217, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14082217.

Lakhani, Nina, and Nina Lakhani Climate justice reporter. “Revealed: How US Transition to Electric Cars Threatens Environmental Havoc.” The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2023, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/jan/24/us-electric-vehicles-lithium-consequences-research#:~:text=The%20US.

McDonald, Loren. “EV Sales Forecasts – EVAdoption.” Evadoption.com, 2019, evadoption.com/ev-sales/ev-sales-forecasts/.

Meegoda, Jay N., et al. “End-of-Life Management of Electric Vehicle Lithium-Ion Batteries in the United States.” Clean Technologies, vol. 4, no. 4, 14 Nov. 2022, pp. 1162–1174, https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol4040071. Accessed 26 Nov. 2022.

newscientist. “Are There Any Lithium Battery Alternatives?” New Scientist, 2022, http://www.newscientist.com/question/lithium-battery-alternatives/.

Price , Brant , et al. “Life Cycle Costs of Electric and Hybrid Electric Vehicle Batteries and End-of-Life Uses.” Ieeexplore.ieee.org, 2012, ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6220712. Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

Tabuchi, Hiroko, and Brad Plumer. “How Green Are Electric Vehicles?” The New York Times, 2 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/03/02/climate/electric-vehicles-environment.html#:~:text=Broadly%20speaking%2C%20most%20electric%20cars.

Times, International New York. “EVs Start with a Bigger Carbon Footprint. But That Doesn’t Last.” Deccan Herald, 2022, http://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/evs-start-with-a-bigger-carbon-footprint-but-that-doesn-t-last-1156240.html. Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

Leave a comment