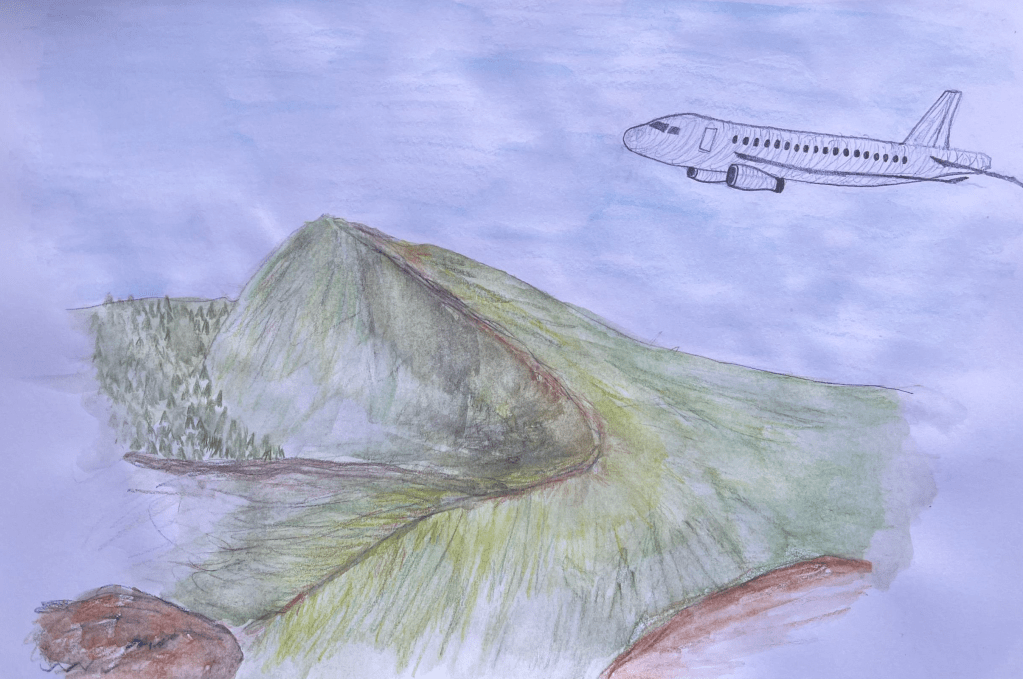

Words by Kiki Shahida, Art by Zoe Graham

Two years ago, I was presented with the incredible opportunity of travelling to the Balkan Mountains and hiking across Albania, Montenegro, and Kosovo for ten days. Because of conflicts in the late 20th Century, this region remained sheltered from the rise of globalization, and thus today is home to a largely unscathed corner of Eastern Europe. The daunting summits, vast forests, blue lakes, and rolling mountains were incredible. I am fortunate to have witnessed such vast nature, almost entirely desolate of anthropogenic activity, something that is today both a privilege and a rarity.

Tour guides led the way as I, and some peers from St Andrews, set forth on our trail through the mountains. Our guides, both self-proclaimed “mountain-men,” knew the routes like the back of their hands—without maps, cell service, or even physical paths on some portions of the trek. Hours of hiking were filled with stories of how they had spent their whole lives outside on these trails, leading all sorts of people across the mountain range all year long. The mountain-men shared a contagious love of the outdoors and thus gratefulness for their jobs, which supported a nine-to-five forest-bathing experience.

However, the tour guides also spoke of the implications their jobs might have upon their naturally rich home. They told us how if we had visited five years prior, we would have been looking at an entirely different landscape, and they spoke worriedly about what another five years might bring. Though not acutely obvious to a Westernized eye, the small signs of urban development were abundant; most villages we stayed in had one or two older-looking little guest houses which welcomed us every night, but these were surrounded by construction for taller, larger, more modern hiking-hotels, soon ready to welcome large numbers of travelers. Between Albania, Montenegro, and Kosovo, I hiked to spots that were quite far off the beaten path, and the mountain-men expressed their concern that these spots were becoming less so each year.

This presents a paradoxical dilemma: tourism as an industry supports these mountain-men and others across the Balkans but has the potential to destroy the industry’s biggest selling point, the environment. On the pro-side, tourism can indeed bring steady economic growth to less developed areas. In small island developing states, like Seychelles or the Maldives for example, tourism has been seen to foster growth and development and provide regions access and connectivity to the global economy. Tourism creates jobs, develops infrastructure, and allows beneficial cultural exchange, all which feed into overall wealth and economic growth. That said, a problem persists in relying too much on tourism, especially in small island nations. Plus, per the focus of this article, tourism is a huge driver of environmental degradation, from air pollution, to litter, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and destroyed ecosystems, the list goes on. How can anyone, from the Balkan mountain-men to top-players in the tourism industry embrace the benefits whilst grappling with the consequences of tourism?

The dilemma of tourism is not unique to the Balkan Mountains, as the pros and cons of tourism have, especially in the last two decades, garnered much attention in the news. Take Venice, for example, home to 55,000 permanent residents, but forced to accommodate upwards of 120,000 tourists on the average summer day. And there’s been some recent policy response: at COP26 in Glasgow leaders declared the need for sustainable tourism, focusing on the importance of lowering carbon emissions and connecting with locals.

One can easily argue that tourism is an essential growth driver and worthwhile investment, especially in less developed regions, yet the counter argument stands that tourism is unsustainable and people should refrain from travelling, especially in wasteful manners. So, should tourism be stopped? Is eco-tourism the solution? Is there any way to travel that is completely sustainable? Can the economic potential of tourism be replaced by a more environmentally sustainable industry in parts of the world with rich natural value? These questions plague Sustainable Development tutorials at St Andrews as much as international policy discussions like COP, all in search of an answer for them before it is too late.

Leave a comment