Words by Grace Brady, Art by Defne Celiktemur

Fisheries monitoring analysts can remotely observe vessel movements in real-time from thousands of kilometres away. They observe vessels sheltering in protected bays during forecasted storms and moving at a slow, continuous pace when pulling a trawl net. This remote monitoring creates a “vessel footprint”, which offers insights into at-sea activity. When two vessels are observed coasting next to each other, slowing to 1-2 knots, or stopping altogether, it’s not just to say hello. An at-sea transshipment is likely occurring.

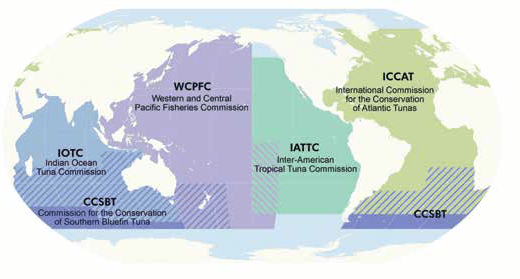

The vessels that participate in high seas fisheries can prolong returning to port because of transshipment, which is defined by Global Fishing Watch as the transfer of catch between vessels, usually from fishing to refrigerated cargo vessels. Due to the global depletion of inshore fish stocks, commercial fishing activity has progressively expanded offshore, beyond areas of national jurisdiction. The United Nations Law of the Seas (UNCLOS) stipulates that a countries’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ) does not extend beyond 200 nautical miles. The areas outside of these bounds are considered high seas fisheries, which are governed by multinational bodies known as Regional Fisheries Management Organisations, or RFMOs.

Globally, RFMOs have not agreed on the best practices regarding transshipment monitoring in high seas fisheries. Transshipment minimises a fishing vessel’s urgency to return to port, reducing fuel costs and allowing catch to enter the market faster, while prolonging fishing effort. However, catch reporting and documentation during transshipment is not standardised, and varies widely between geographical region and target catch species. This creates loopholes in supply chain transparency, from where a fish is caught to where it is landed in port. Fish caught through illegal, unreported, or unregulated (IUU) practices can mix with legally obtained catch during transshipments, and enter the market, a process known as fish laundering.

Beyond perpetuating IUU catch entering global markets, transshipment has negative impacts for people working in the fishing industry. Predatory captains withhold payment and passport documents for crew members, forcing people into modern slavery at sea. Transshipment vessels are utilised to transfer crew between fishing vessels, which can keep people at sea indefinitely. Within the scope of workers’ rights at sea, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) is only applicable to workers on merchant vessels, failing to protect workers susceptible to human rights abuses on fishing vessels.

Beyond negative impacts on labour in high seas fisheries, understanding the variance in transshipment regulations adds to the murky nature of this practice. The variety of regulations can be better understood through a prominent global fishery: tuna. As a target species, tunas are highly migratory, meaning that most commercial fishing efforts occur in high seas areas, as outlined by the global reach of tuna fishing in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Map of RFMOs that Participate in Tuna Fisheries

In tuna fisheries, transshipments are required to be monitored by independent observers placed on the receiving carrier vessel, in addition to requirements for observers onboard a certain percentages of fishing vessels. The regulations don’t just relate to at-sea transshipments, and include various requirements related to reporting and monitoring of transshipments in ports. However, much of this advice is issued as voluntary guidance, which creates a lack of enforcement accountability.

While the risk of transshipment enabling IUU catch to enter markets are known in all the tuna-focused RFMOs, guidance around transshipment varies between them. For example, both the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) and the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) require a Record of Carrier Vessels permitted to tranship tuna, but CCSBT prohibits carrier vessels from transshipment that are authorised by other RFMOs to do so. Both have similar guidance on the importance of observer coverage, with ICCAT implementing the first regional observer coverage for at-sea transhipment. Priority during port inspections of landed catch is focused on vessels whose Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) or Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals disappear without explanation between transhipment and entering port.

To further minimise misreporting during transshipment, RFMOs like CCSBT and ICCAT have stringent guidelines for declaring transshipments to their respective Secretariats (the centralised management body of an RFMO), which is required by both the fishing and cargo vessels. These declarations are time-sensitive, and are frequently issued within 48 hours of a transshipment, documenting the catch, location, and flag states of the participating vessels. While these regulations offer clarity around transshipment activity, the process of RFMOs to implement further changes in frequently stumped by consensus-based decision systems. A singular dissenting opinion will halt the passing of a new conservation measure, enacting change slowly over time.

At-sea transshipment affects nearly all aspects of the commercial fisheries trade, from net to plate. In 2017, academics and industry professionals called for a moratorium on transshipments in high-seas fisheries, due to difficulties in enforcement and regulation. However, the increasing global demand for seafood means this practice is likely not slowing down anytime soon. A sustainable future for at-sea transshipment requires the support, communication, and resources of multi-national bodies to further incentivise compliance and push for regulations that are mandatory, not voluntary.

Leave a comment