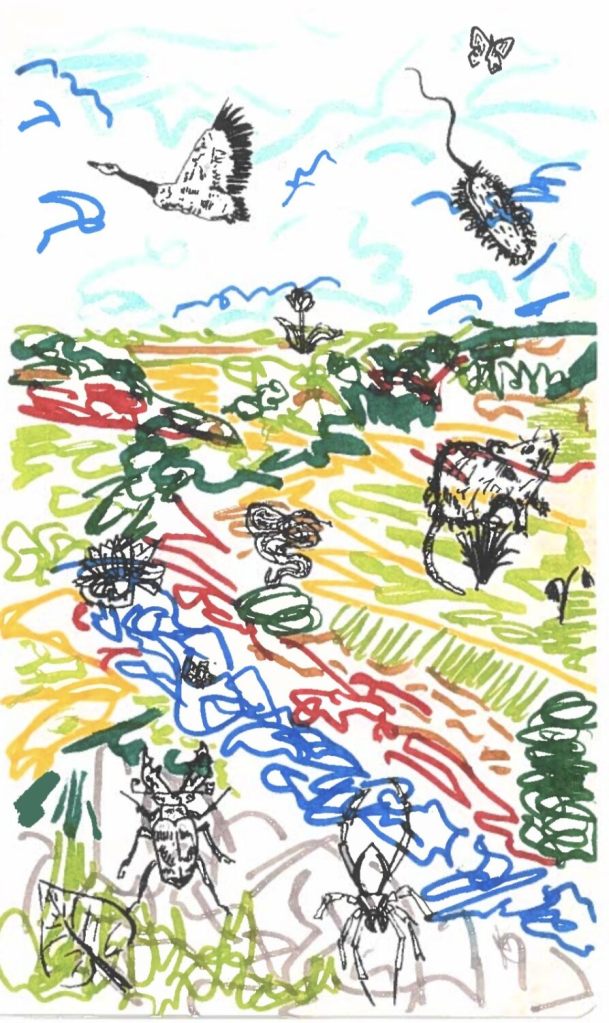

Writing by Em Challinor – Art by Ester Burgerova

What writing do we need in a time of crisis?

Emergency, by Daisy Hildyard, is described in the subtitle to its American edition as a pastoral novel. We enter its English village setting through a child’s eyes, watching a kestrel hunt a vole on the floor of a quarry. While the quarry is central to the childhood world of the novel, it is also at the centre of a web of global trade, exporting slate to China to be made into roof tiles as transnational corporations fight for its ownership. The rapturous attention that captures the kestrel ‘like a camera’ also captures the plastic in the river and the fight for the quarry. As we weave in and out of the narrator’s childhood in the village, resurfacing periodically in the present where she writes from her lockdown flat, we pick up strands of other stories: the family of foxes living by the river, a man who has run away from the army living in a nylon tent, the plastic cup from his pot noodle, made in China yet marked with an English country scene. Hildyard describes her want to expand beyond one story, revealing the detail at every point on a continuum of scales of which a human life is only one. The novel updates the pastoral form to encompass all aspects of a messy, non-innocent, natural-human world.

It seems that teaching-to-see is a central project of environmental literature. The child-gaze of Hildyard’s narrator facilitates voracious noticing which magnifies detail and takes others seriously. Expand this form of noticing into your own life, really pay attention to something, and it seems hard to stop yourself from caring at least a bit. Once you notice the foxes in your garden or the plastic cups in the river, they become part of your world and you part of theirs – you are bothered, involved, in their business. ‘Everything shapes what it encounters’. When you notice other lives and other systems, you notice your impact on them, and this seems to go some way towards enabling responsibility.

Yet seeing connection is only the start. Visibility and cohabitation with other beings means mutual vulnerability, and room for ambivalence, and the novel has room for violence as well as care. The narrator recalls scooping a young rabbit from a hutch with the knowledge that her smell in the nest would drive the mother to eat her babies, returning to find her massive and alone and revelling in a feral kinship. This too is entanglement and responsibility. There is not a straightforward relationship between seeing others, caring for them, and collaborating in a way that enables mutual survival. People, as well as rabbits, are driven by conflicting desires and destructive urges as much as urges to care. Further, even when awareness leads to the desire to ‘help’, there is a limit to the action that is possible. The battle over the quarry can be observed, but the process of filling it in which drives out the sand martins and peregrines cannot be stopped. Seeing the global systems woven into your local web could easily lead to despair when there is little hope of changing them. Seeing the dazzling complexity of interconnection could lead to overwhelm. We need more. What do you do upon seeing the web of violence you are knotted into? It seems that seeing alone can only get you so far.

At the end of the novel, just as we are about to emerge, the narrator breaks out of her reverie to the smell of smoke, realising that her apartment block is on fire. It is a shocking awakening. One reading of this ending is as an obvious warning and self-critique. The novel aims to reveal ‘slow violence’ through attention, yet the fire demands action now, whether or not we have had time to adjust our ways of seeing and living. The opposite of slow violence, the fire is immediate and all-consuming. It combusts the tree on the street corner, forcing ‘everything living to get out of there’. Emerging from the novel as the narrator emerges from her reverie, we might ask whether we are also emerging into a burning world. For many, climate change has brought about more than slow disaster, it has destroyed lives and homes. Is it indulgent to focus on slowly changing how we perceive the world, when it is a luxury to be subject only to slow violence rather than the catastrophic destruction that threatens many?

Amitav Ghosh, author of The Great Derangement, calls for a climate literature that can account for the vast global scale of catastrophes and the collective action they demand. He argues that the form of the novel, focused on an individual moral journey, is ill-suited to deal with the ‘epic’ reality we face, where damage is sweeping and global in scale. Are we looking at the wrong scale here, watching the bugs on the window-box plants while the building burns down?

Perhaps. But perhaps there is room for a synthesis of the two approaches. While changes happen on a global scale, we are – for better or worse – limited to the local and the personal in our daily lives. Hildyard, and climate literature generally, could provide hope for a kind of emergent action – small acts, motivated by attention, aggregating to make a difference. We are always going to have to act on a personal scale, yet we need to imagine how these actions could impact something bigger. Literature can help us to do that.

Leave a comment