Writing by Emma Nelson – Art by Ester Burgerova

Every day, perfectly good food ends up in the trash– half-eaten dinners scraped into binds, misshapen vegetables tossed aside before they ever leave the farm. And yet, millions of people around the world still struggle to eat. More than 780 million people endure chronic hunger, with a third facing such extreme food shortages that their lives are at immediate risk. The constant struggle to find the next meal takes a drastic toll on health. Children in food-insecure households experience two to four times more health issues than their peers, often suffering from cognitive impairments that make it harder to succeed in school. Meanwhile, adults without access to nutritious food face higher rates of chronic illnesses like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and kidney disease.

Widespread food insecurity is not just a matter of poor distribution. It is intertwined with systemic failures that contribute to environmental injustice as well. Communities disproportionately affected by pollution, industrial waste, and environmental neglect are often the ones likely to be food deserts, areas where fresh, healthy food is virtually inaccessible. In the US, research has consistently shown that low-income and predominantly communities of color have fewer grocery stores, replaced by closer fast-food chains and local convenience stores selling highly processed foods. For many residents, accessing fresh produce requires a commute costing gas money and time often unaffordable among work, childcare, and other responsibilities.

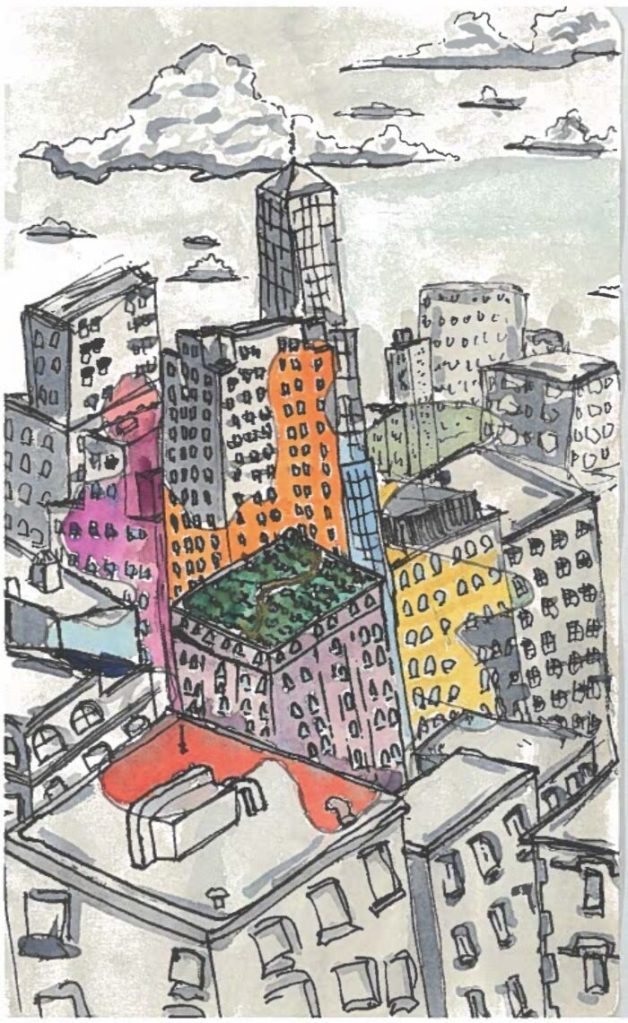

In response to this systemic failure, many communities have taken food access into their own hands, adopting the idea of food sovereignty. Food sovereignty goes beyond food security by emphasizing the right of people to control their own food systems, from production to consumption. According to the US Food Sovereignty Alliance, this means not just having access to food, but food that is nutritious and grown in ways that sustain both the land it stems from and the people that sow it. In many disadvantaged areas, urban farming has emerged as a direct response to food deserts and environmental inequity. Reclaiming abandoned lots and neglected spaces, these gardening initiatives not only provide fresh produce to local neighborhoods, but work to create green spaces in polluted areas, reduce carbon emissions from food transportation, and reduce food waste.

Urban farming is far from new. Ancient Mesopotamians and Persians laid out pieces of land within their dense cities to grow food for locals and manage urban waste. The practice has grown from these beginnings, booming during the 2008 recession, and again during the pandemic. Today, urban agriculture takes many forms, from herbs being grown on apartment balconies and backyard carrot patches to rooftop greenhouses and fully fledged community gardens. Some community gardens, such as Grow NYC, even partner with local farmers to source fresh produce that local residents can pick up at designated distribution sites near the plots. Initiatives such as this provide sustenance both in the form of physical food and a strengthened sense of community and resilience.

Grassroots, community-led efforts to combat food and environmental insecurity are making a powerful impact. However, this should not belie the importance of acknowledging the systemic and policy failures that have made these initiatives necessary in the first place. Food deserts are not accidental, but the result of intentional policies and disinvestment that have limited access to healthy food in low-income communities and communities of color. While food assistance programs have been implemented to help address hunger, they are often too restrictive and don’t serve enough people. Strengthening these safety nets is the first step to alleviating hunger, improving public health, and reducing economic disparities. But policymakers must also look at the broader picture and address the root causes of food insecurity, reforming the policies that perpetuate systemic inequality and widening access to resources and opportunities.

Achieving long-term, equitable access to food requires not only addressing these policy challenges, but ensuring that food production systems are resilient and adaptable to future demands. As climate change accelerates, policy measures unfortunately may fall short of meeting the immediate needs of communities. Initiatives such as community gardens are more important than ever in connecting food justice to environmental sustainability. From reducing heat island effects to restoring soil health in neglected urban areas, these gardens offer a number of environmental benefits. More importantly, they empower local residents, giving them the tools to take control of their food systems and foster resilience in the face of climate challenges. In doing so, community gardens become a powerful grassroots tool in playing even a small part in addressing food security, environmental degradation, and systemic inequality.

Leave a comment