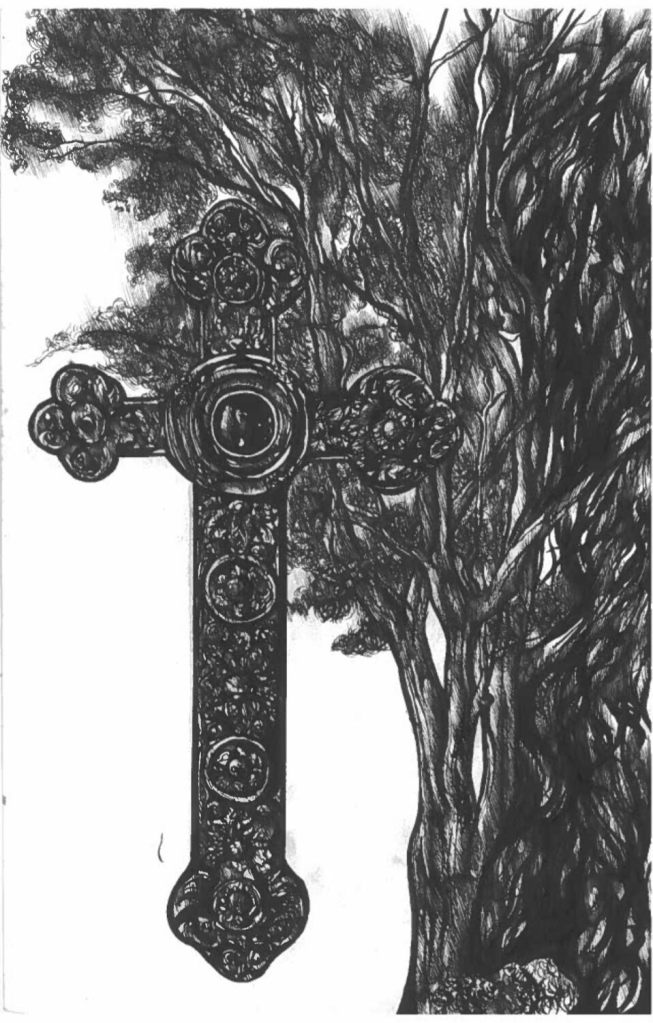

Writing by Danae Evans – Art by Lucia Assadi

The climate crisis is often framed as an issue of science or politics, but ecotheology — the study of environmental concerns in the context of religion – offers an alternative framework for understanding its origins. Ecotheology presents the climate crisis as an issue — or rather, a product – of spirituality and cultural belief systems. In particular, Christian ecotheology highlights the influence of Christian values in shaping Western practices, laying the foundations for industry, expansion, and exploitation — the very systems driving our climate crisis. The legacies of Christianity are complex, but in light of growing climate apathy and denial, studying Christian ecotheology can offer a new perspective on the roots of environmental exploitation. To address the climate crisis from the root up, we have to think critically about our understanding of humanity’s place in the natural world – and challenge the mindsets that have shaped it over the years. Tracing these theological ideas from the biblical text, through medieval Christianity, and into the Reformation, we begin to see the evolution of a worldview that shaped Western attitudes toward nature.

Exploring the origins of Judeo-Christian climate dogma leads us to the Book of Genesis, both the first book of the Torah and the Christian Old Testament. Specifically, in Genesis 1:26-1:28, man is created in God’s image and granted “dominion” over nature in all manifestations. Dominion is a key piece of language in discussions of Christian ecotheology, as dominion presents the idea of control, in this context, over nature. This idea that nature was created for man’s benefit can excuse harmful and unsustainable environmental treatment for the purpose of convenience or personal gain, and this engrained mindset is at the core of modern industry and technocracy. In a similar vein, it’s worth considering how the Bible frames man as the only one of God’s creations made in His image. Some ecotheologists argue that this presents man as superior to His other creations, i.e. the natural world, feeding into the same harmful culture of entitlement. While this argument is at the core of an ecotheology critique of Christianity, it’s not the only definition of man’s relationship with nature presented in the Bible.

Within the same book (Genesis), the Old Testament discusses man’s responsibility to serve and tend to the Garden of Eden. This theme of “stewardship” is maintained throughout both the Old and New Testaments. Stewardship presents an alternate understanding of natural themes in the Bible; man is responsible for caring for and protecting the natural world. As upstanding and noble as this mentality may sound, is it a truly healthy understanding of our relationship with the natural world? Stewardship still feeds a hierarchical mindset, implying that man has control over the environment. Consider the central role of Christianity in European settler colonialism and think critically of the European fixation on learning to improve the climate or understand climates as a means of controlling people in their colonies. For example, European settlers in North America believed that deforesting and draining swamps would transform the harsh climates of the East Coast into a more temperate one, and framed climate control as central to their narrative of ‘civilizing’ both the land and indigenous peoples. It is not unreasonable to connect this urge to tame the land with the environmental control presented by stewardship, to explain the road to exploitation paved by Biblical values. A very different criticism of Biblical stewardship is based on the fact that the word “stewardship” only appeared over 1600 years after the death of Christ, prior to which, the main understanding of the Biblical view of the environment was dominion.

Biblical ecological perspectives really took hold as Christianity spread throughout medieval Europe; and would continue to evolve with the transformation of Christianity during the Protestant Reformation. As Christianity overtook various Pagan belief systems, it began to replace animism – the idea that all natural objects, both living and inanimate, have a soul – with dominion. Animism is central to many pre-Christian ecological beliefs. Though humans have hunted or altered their environments for millennia, animism maintained a cultural understanding of kinship. Fast forwarding to the Protestant Reformation, the transformation of Christian values further altered the understanding of the relationship between man and nature. Through the lens of ecotheology, the rise of Protestantism and the development of capitalism and technocracy are directly connected concepts. The fundamental perception shift behind this development has to do with the shift from belief-centered faith (Catholicism) to action-centered faith (Protestantism). The sacraments and spiritual devotion prioritised by Catholicism were replaced by moral and practical living promoted by the Reformation. In simple terms, this promoted a culture where devotion to work was seen as an expression of religious commitment, which closely aligns with the “spirit” of capitalism. Lynn White Jr., a central scholar in ecotheology, describes this as an “implicit faith in perpetual progress” – a mindset unique to Judeo-Christianity that has greatly shaped our current culture of development, driving capitalist expansion and the exploitation of the natural world. It’s also worth considering the correlated geographic origins of capitalism and Protestantism, both originating and spreading out of Northern Europe. During the Reformation, this region also saw a rise of private property replacing church-owned and communal lands, redefining land as a commodity. Another psychic shift of the Reformation was a shift from external rituals to internal moral faith, reducing the significance of the physical church. In the ecotheology view, this detachment reflects a larger cultural detachment away from the sanctity of physical spaces; and is manifested in a growing separation from nature.

While not directly harmful to the environment, Christianity and the Reformation are a crucial part of the spiritual foundations of industry, the consequences of which have been devastating to nature. This passage shouldn’t be understood as a critique of the religion as a whole. The Bible also presents ideas of punishing those who abuse the natural world, and condemns cultures of greed or apathy – morals that should feed environmentalism. Faith-based advocacy is an important pillar of change, fostered by various sects of Christianity for example. Rather, it’s vital to understand the misuse of Christian values that have set foundations for capitalism, technocracy, and the climate crisis – and challenge these values to address the climate crisis at its core.

Notes:

“Man” is used in this paper in keeping with the usage in Biblical translations. Its usage is gender-neutral and synonymous with “humanity” or “humankind.”

Leave a comment