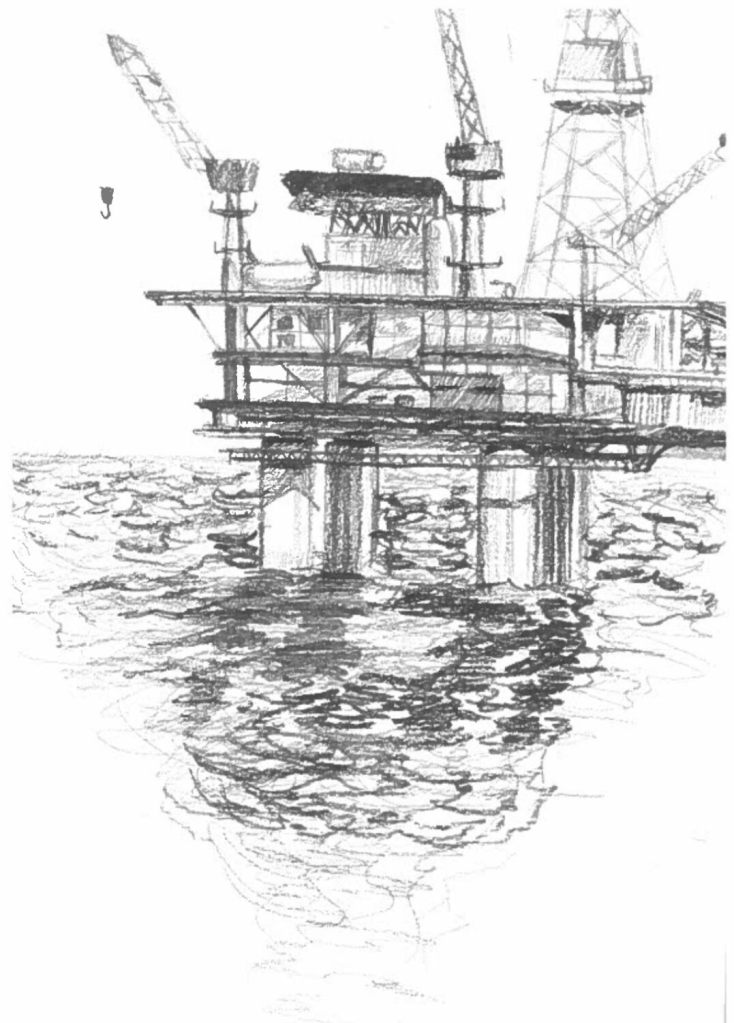

Writing by Ash Brennan – Art by Caroline DaSilva

There are approximately 12,000 offshore oil and gas platforms globally, and many of these will need decommissioning in the coming decades. With decommissioning costs mounting, oil and gas giants may look for alternatives to full removal of infrastructure. The conversion of platforms to artificial reefs has repeatedly been put forward as an option, but so far has gained little traction outside the United States.

In the North Sea alone, companies expect to spend £24 billion on decommissioning activities in the decade to 2032. Operators in this area have been warned to secure their supply chains in preparation for the coming glut of rigs reaching the end of their life, after consistent delays in the decommissioning of infrastructure in the North Sea. In Australia, the federal government was forced to take responsibility for decommissioning the Northern Endeavour oil platform after the costs associated with cleaning up the site forced the company operating it into liquidation in 2020. The complexities of the Northern Endeavour mean that the total bill could exceed A$1 billion, or £487 million (the Australian government has imposed a levy on the industry to fund this).

Offshore oil and gas decommissioning represents a large cost to companies operating these structures after the revenue streams derived from them have dried up. With costs mounting, and under pressure to shut down greenhouse gas generating energy sources prematurely, companies are likely to look for ways to save money on the clean-up bill. One method that stands out is the practice of converting former oil and gas rigs to artificial reefs.

Known as ‘Rigs-to-Reefs,’ this practice is common in US waters. In the Gulf of Mexico, approximately 600 rigs have been converted to artificial reefs since the 1980s. In each case, the oil well itself must be capped, and the structure altered so that it no longer poses a hazard to navigating ships. This means toppling the entire tower or cutting off the top to be sunk beside the base. The idea is that the physical structures of rigs become inhabited by many species of anemones, muscles, barnacles, and other bottom-dwelling organisms. These, in turn, support fish and other animals.

In addition to the potential ecological benefits, the Rigs-to-Reefs process also offers oil and gas companies significant savings over the alternative (full removal of infrastructure). These factors have contributed to high uptake of the process where jurisdictions permit, and in a few notable cases, the limits of regulations elsewhere have also been tested.

In 1995, Shell provoked public outrage when their plan to sink the Brent Spar floating oil platform in the North Sea came to light after it had been approved by the UK government. What followed was a highly publicised occupation of the platform by Greenpeace and public backlash against Shell. The plan to dump the structure in the ocean was eventually abandoned, and these events have shaped policy and opinions on decommissioning in the North Sea since.

A similar story played out more recently in Australia. In 2021, the oil giant Woodside released a plan to sink and make an artificial reef out of their Riser Turret Mooring (a floating oil platform) near Ningaloo reef, a world heritage area in Western Australia. At the time, Woodside said a design mistake and a lack of maintenance caused problems, which meant the platform could not be fully removed. The proposed plan involved towing the platform towards Ningaloo Reef and sinking it in order to create an artificial reef. However, concerns were raised about various pollutants contained within the structure, which could potentially escape into the marine ecosystem. The plan was eventually abandoned in favour of full removal.

Part of the reason these Rigs-to-Reefs projects keep being proposed is because there is merit to the idea in certain circumstances. Studies (generally focusing on fixed oil rigs rather than the floating structures of Shell and Woodside above) have found the struts of oil rigs to be the most productive of marine environments and to form important nursery grounds for fish species. Proponents of the Rigs-to-Reefs scheme put it forward as a silver lining that can be exploited to positively affect ocean ecosystems. However, such proponents also point out that not every offshore platform is suitable for reefing.

Toxins leaching into the environment is one concern put forward by those opposing Rigs-to-Reefs conversions, and some structures pose more of a risk than others. Scientists have also expressed doubts about the true ecological value of these structures, for instance whether they really increase the biomass of some fish species or simply aggregate them from the surrounding area. Another concern raised by scientists is whether invasive species can spread more easily through networks of artificial reefs.

A through line in opposition to these projects is the sense of justice that petrochemical giants should pay to return the ocean to a pristine state after they have been using it for profit for so long.

Scientific research is ongoing, but in the meantime, Rigs-to-Reefs projects are happening, and companies will continue to suggest them where money can be saved. Looking ahead to the coming decommissioning wave, companies should not use the Rigs to Reefs concept as a last resort when complete removal is expensive or technically challenging; conversions should only be considered when they present a clear benefit to the environment.

Leave a comment