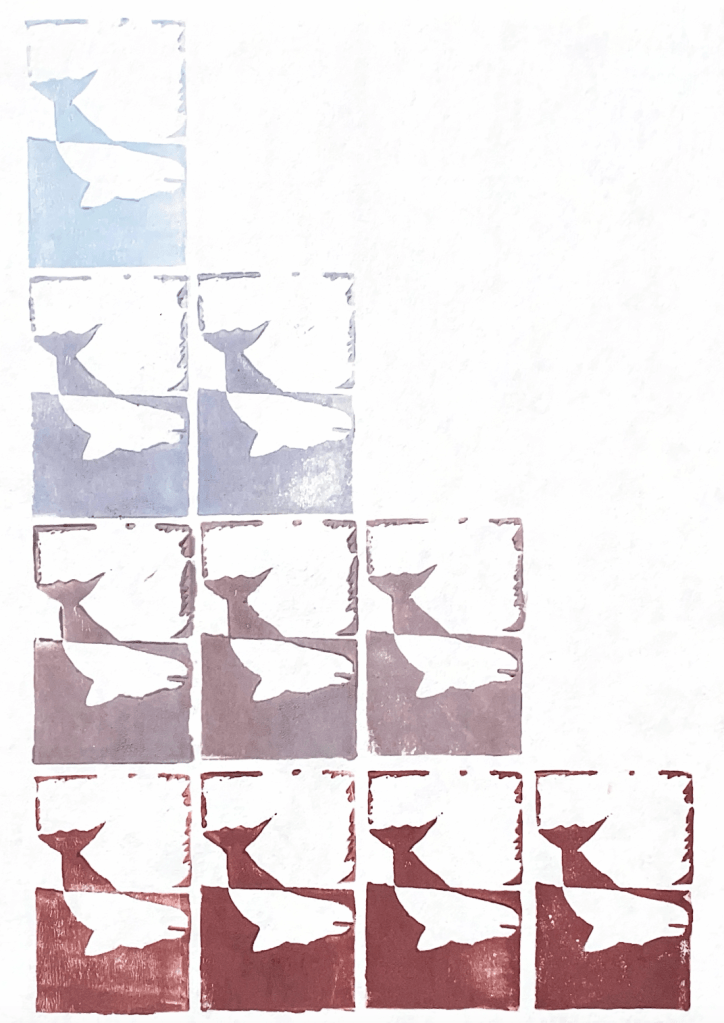

Writing by Anokhi Saha – Art by Nora Krogsgaard

Upon starting my research into how climate change is impacting whales, the very first article I encountered was entitled “Too Hot for Humpbacks”, courtesy of BBC News. Scrolling not much further, I came across the Whale and Dolphin Conservation’s website detailing the staggering declines in habitat and prey species. And shortly following that is the WWF’s shocking statistic that “as many as 300,000 whales, dolphins, and porpoises are killed every year from entanglement in fishing gear”, a figure that is expected to worsen as sea ice declines and more fishing channels open in key feeding habitats. A lot of stories of doom and gloom, and not a lot of good news for our marine mammals.

Focusing specifically on Arctic cetaceans paints an even worse picture. The Arctic is one of the most vulnerable ecosystems under threat from climate change as a result of polar amplification. Sea surface temperature (SST) is warming at twice the global average rate, with a decline in sea ice of 75% since 1980. The Arctic is a key habitat for 17 species of whales, as the icy waters are some of the most productive and prey dense of anywhere in the world. While most of these species undergo enormous migrations across the globe for the chance to feed here, there are just three species that remain year-round: beluga whales, narwhals, and bowhead whales. These species are thought to be particularly vulnerable as a result of the complex feedback between the temperature, ice coverage, and prey density. However, the incredible adaptive capacity of these cetaceans is widely underdiscussed, despite the hope it provides.

Beginning with bowhead whales, these iconic inhabitants of the Artic are easily recognised by their distinctive baleen plates which allow them to filter feed up to two tons of zooplankton (krill) per day. As temperatures warm, the primary prey species for the bowheads has been greatly diminished due to their reliance on sea ice throughout their lifecycle. However, these species are being rapidly replaced as more temperate species move northwards, and the bowheads are profiting from this alternate prey source. Whilst these new species have been affectionately termed ‘Junk Food’ by scientists due to the reduced calorie content, the whales have adapted to overcome this challenge too. Some groups are compensating by adapting their patterns of diving to increase the time they spend feeding, while others are drastically altering their migration routes to track their preferred prey to higher latitudes. The bowheads have also been able to profit from previously inaccessible prey patches due to the declines in sea ice, showing remarkable behavioural flexibility. It is this incredible resilience and plasticity shown by the bowheads which may have enabled their survival ten thousand years ago, when global climatic changes drove mass extinctions across both marine and terrestrial realms. And it is this same plasticity which may be key to their persistence at present. Since the end of commercial whaling in the 1900s, the stocks of bowhead whales have rebounded, with population growth continuing despite the additional challenges arising as the climate changes, a testament to the resilience of this species.

But bowheads aren’t the only species capable of such adaptation in the face of adversity. Both belugas and narwhals depend upon Arctic cod as a pivotal yet diminishing prey resource. And yet both species have been found to exhibit more behavioural plasticity to prey scarcity than previously thought possible. Stocks of belugas across the Arctic have all been found to have a remarkably high level of flexibility in their diet, swapping between cod and capelin as fluctuating prey densities dictate. Narwhals similarly show plasticity in their foraging, with new studies showing increased consumption of Greenland halibut and analysis of their tusks providing evidence of previously unknown dietary flexibility. This is truly remarkable given the high levels of adaptation needed in order to survive in such a harsh environment such as the Arctic.

However, this isn’t to say that the fate of these iconic species is by any means secure, as switching to less profitable prey sources are expected to have serious long-term population wide impacts. Furthermore, species already operating at their physiological limits only have a certain capacity to further adapt, especially to such unprecedentedly rapid changes. That is not to mention the impact of direct anthropogenic activities such as shipping and fishing which further threaten the species survival.

And yet, there is still hope. All three species have shown a remarkable capacity to respond and persist in the face of their changing environment. This is not only a truly impressive feat that deserves to be celebrated, but also a source of hope for the fate of our Arctic cetaceans. These animals are not passive inhabitants of their environment, they are active participants, adapting and innovating in ways we are only just beginning to understand. Their stories remind us that resilience is still possible, even in the most unforgiving places on the planet. But their future is not theirs alone to shape, it depends on the choices we make now. With continued research, effective conservation, and a renewed global commitment to protecting the polar regions, the next chapter for these whales could be one not just of survival, but of recovery and renewed success.

Leave a comment