Words by Sky Maher, Art by Siobhan Henderson

There are few people in the world experiencing the effects of climate change more rapidly than the Saami in the Arctic circle. The Saami people are indigenous to Sámpi, the collective term for the arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. This population of around 100,000 is acutely at risk as temperatures rise.Their home within the Arctic means that they experience climate change four times faster than the rest of the world, and their proximity to nature makes themadditionally vulnerable. The world of the Saami is one dominated by the arctic snowscape. Their culture, as well as their livelihood, is centred around the snow. This intimacy is evident in the 360 words that the Saami have to describe snow and precise classification systems for the different kinds of snow (such as ‘sabekguottát’, meaning snow with a frozen crust). Snow once covered Sámpi for eight months of the year. Now, with the 2.3 degree increase in temperature, it is melting as well as falling in fewer quantities. These shifts have exposed the Saami to an increase in precipitation pollutants, one of many adverse effects of a melting home.

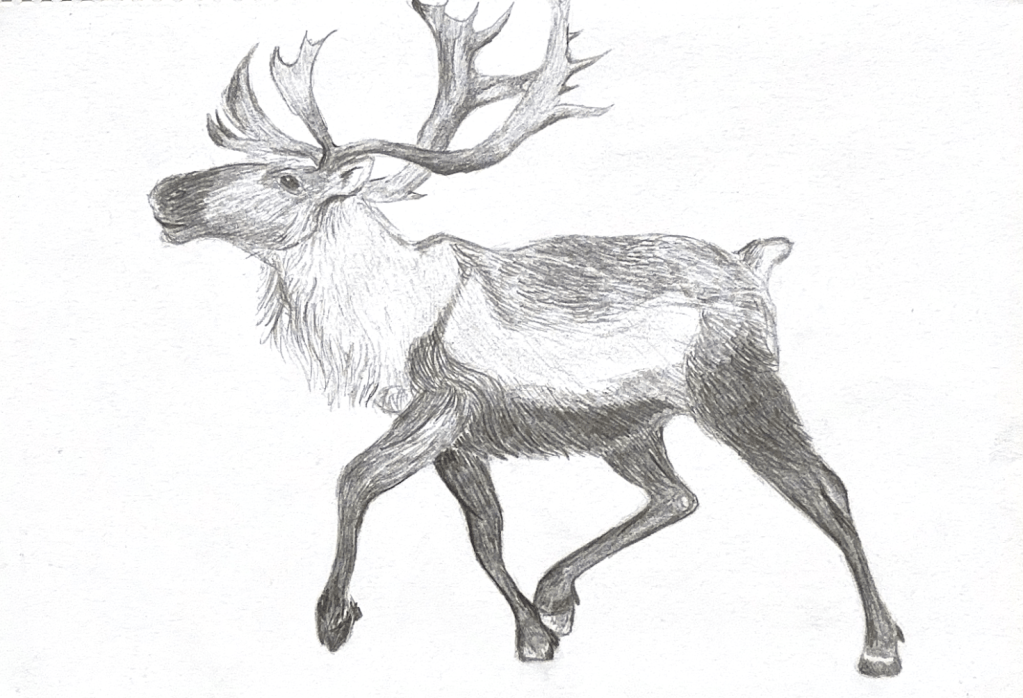

As well as directly damaging to the population itself, the snowfall changes are catastrophic to the reindeer herds that sustain the Saami people. An estimated 2.5 million domesticated reindeer rely on the snowfall and specific winter conditions to survive. As well as supporting the Saami, the reindeer play a key role inprotecting the Arctic’s tundra biome by grazing on shrubs and lichen. Without this, the shrubification of the tundra would introduce more heat into the frozen ecosystem , increasing instability in an already fragile world. The reindeers’ grazing is also vital for its role in maintaining the open arctic forests. Yet these vital processes are not possible with the frequent thaws and refreezing that create impenetrable ice crusts above the grazing ground.

This shift in weather spells much danger for one of the Saami’s core cultural practises, and risks accelerating the transition from a traditional to modern-industrial way of life. This transition has already been felt by many with the introduction of modern equipment such as snow mobiles and other machinery that many of the Saami are now reliant on. As the patterns of snow fall change the husbandry of the reindeer, there are growing concerns for these ancient communities and the survival of their cultural practices. The vulnerability of the Saami population and its culture is visible, as many young Saami people shift to more urban locations. Additionally, there has been an increase in the uptake of Finnish and Swedish, with only half of the Saami people now speaking the traditional language. Thesefactors have been key to the classification of all ten of the Saami languages as endangered or highly endangered.

The urgency to protect not only the Arctic climate but the Saami’s culture and traditional practices is particularly apparent to the many Saami communities who rely on continuation of oral languages and stories in the absence of written history. Within these ancient and oral histories of indigenous communities, a huge portionof the information relates to traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). TEK is a major asset to the globe in the midst of catastrophic climate change and yet many communities and their ancestral knowledge are at a great risk of being lost. Per-Oluf Nutti, president of the Saami Council says, “we know our knowledge is vital to mitigating the effects of climate crisis in our land”, but rather than gaining recognition, the Sammi are having to fight climate change as well as basic issues such as land rights. Saami anthropologist and politician Klemetti Näkkäläjärvi elaborates on this issue, writing that “climate change mitigation and adaptations are a question of human rights for Indigenous people”. They are not only having to fight their melting home, but also for legislation and rights that are crucial for the survival of indigenous communities.

Leave a comment